Just Like in the Pictures

Vincenzo Latronico has written several novels in Italian, but Perfection, published by New York Review Books this week, is his first novel to be translated into English. The book follows the lives of two young digital “creatives” in Berlin and other parts of Europe. Lynnette Widder looks at the book's applicability to architects and what it says about the role of images and social media in contemporary culture.

“Our culture is to a certain extend the product of our architecture. If we want our culture to rise to a higher level, we are obliged, for better or for worse, to change our architecture. […] The new environment, which we thus create, must bring us a new culture.” – Paul Scheerbart, “Glass Architecture,” 1914

“If I write better German than most writers of my generation, it is thanks largely to twenty years’ observance of one little rule: never use the word ‘I’ except in letters.” – Walter Benjamin, “A Berlin Chronicle,” ca. 1900

A fond hope of architecture, and perhaps one compelling reason beyond aesthetics for the perennial appeal of early-20th-century Modernism, is that buildings have the capacity to change those people who inhabit them. The attractiveness of this belief would not surprise the protagonists of Vincenzo Latronico’s novel Perfection, Anna and Tom, a heterosexual couple whose experience of a metamorphizing, early-21st-century Berlin parallels their own growing existential doubts. Equally true of the novel is that, because architectural space, furniture-scale objects, and cityscapes determine the inner workings of the protagonists’ lives, traditional selfhood—the “I”—is absent. Anna and Tom are avatars of the places they inhabit. This means that there is plenty here for architect-readers. They might identify with many of the professional and social malaises in the plot line: the excesses and exploitations of the gig economy, the perniciousness of image trafficking, the role creative practitioners have played and continue to play in the urban phenomenon called gentrification. Even more compellingly, they might revel in the ways interior and exterior vistas exercise control, determining Anna and Tom’s moods, their work, their personal relationship, and, finally, their capacity to envision a satisfying future. Who are the protagonists, the novel asks, the people or the meticulously described spaces?

The book is divided into uneven sections. “Present,” the first, is a six-page description of a Berlin apartment, its furnishings, and the building in which it is located, all easily imaginable by anyone trained in design: “Sunlight floods the room from the bay window, reflects off the wide, honey-colored floorboards and casts an emerald glow over the perforate leaves of a monstera shaped like a cloud.” Or, “The back wall has floor-to-ceiling shelves lined with paperbacks and graphic novels, most in English, interspersed with illustrated coffee-table books—monographs on Noorda and Warhol, Tufte’s series on infographics […]” Because they inhabit this perfectly constructed space, the reader is led to believe Anna and Tom, who met while studying in an unnamed Southern European location, represent the early-aughts ideal of Berlin expat life.

Then comes the section entitled “Imperfect,” about eight-five of the book’s 120-odd pages. It introduces the niggling uncertainty that will ultimately undermine the semblance of Anna and Tom’s picture-perfect happiness. Uncertainty takes the form of dust on plant leaves, clutter on tabletops and armchairs. The windows through which sunlight floods the space “were old and the radiators too small to keep the space heated. Only rarely did they muster the patience and resolve to clean the double-paned windows, which were covered in tiny constellations of milky smudges that would appear brighter as spring turned to summer.” Light, initially signaling largess, now prosecutes the couple’s inadequacies as it highlights the milky smudges that compromise the apartment’s opulent daylight. Within a few pages, the spatial attributes that had established the protagonists’ perfect life have undermined it; discrepancies between the picture-perfect and the rumpled mundane are as unbearable to Anna and Tom as the slow attrition of friends, party drugs, valued leisure, and youth in the city where they had arrived as young digital nomads.

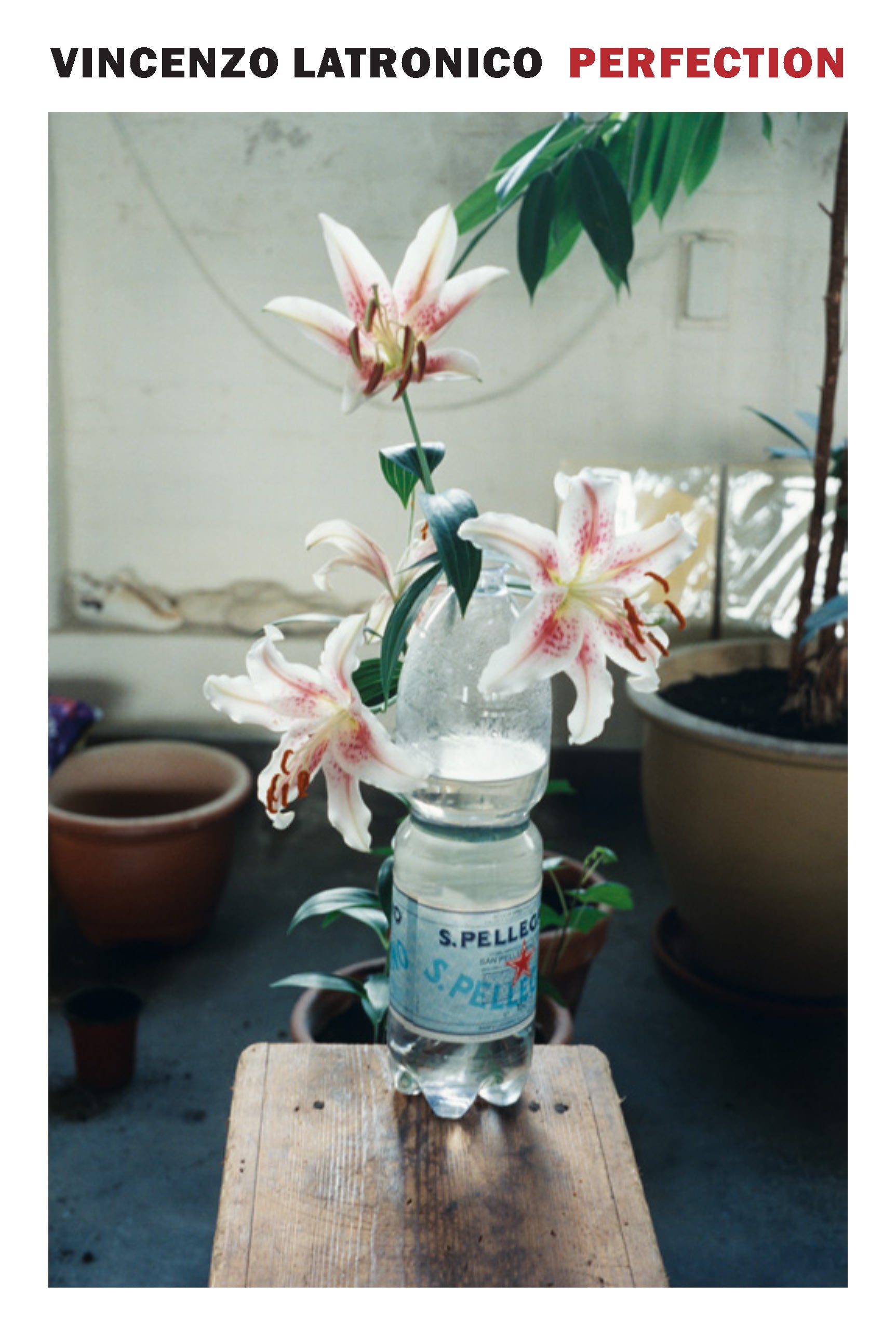

“Remote,” a two-section interlude, finds the disillusioned couple in Lisbon and Sicily, seeking the adventure and promise that Berlin no longer holds. In Lisbon they inhabit a decrepit hotel under renovation, where “the walls were a dusty beige, with brown streaks in several places; the veneer on much of the furniture was chipped or peeling, revealing the moisture-damaged chipboard underneath.” In Sicily it’s an inexpensive ground-floor apartment in an innocuous house where “rows of dead flies stood guard at every windowsill, as light and brittle as pressed flowers. Opening the windows just a crack let in the roar of trucks from the Syracuse-Gela motorway on the other side of the hill.” Just as the light-flooded spaces in Berlin initially made Anna and Tom in the image of the young urban creative, the mediocrity and desuetude of these Southern European spaces undermines them. They bicker; they lose the conviction that the images they make and the life they lead are valid. Although their pictures posted to social media “were always stunning, enticing—prickly pear groves, Camparis on red plastic beach tables […] something in their spirits had changed. Back in the day, looking at images like those and knowing how frustrated and unhappy they had been when they took them made them feel ashamed […] Now those images just seemed like a con.”

The book ends with “Future,” an epilogue initiated by the couple’s deus ex machina deliverance to an inherited farmhouse in an unnamed Southern European country which they transform into a boutique hotel. The ephemeral design work—pastel color schemes, filleted corners, Helvetica light lettering—which had come to bore Anna and Tom is replaced by physical labor and tangible things. There is furniture to build, hand sketches to be made, banyan and rubber trees to be planted outdoors. “The yellowing limestone will be embroidered with creepers; the land will be enclosed by a drystone wall that runs alongside the dirt road leading down to the coast. The air will smell of heat, dust, wild fennel, and salt; the arid, mineral soil will lend a sharpness to the wine and oil produced there.” And yet, after a successful opening weekend, faced with the carnage left by their influencer guests, Anna and Tom can only take consolation not in the prospect of honest labor but instead, in a review posted on social media “It’s all completely perfect, the story will say. It’s just like it is in the pictures.” What architect, the outcome of their efforts ceded to a client, has not also sought solace in images of the spaces conceived and then fought for, photos that show those spaces before they were debased by the people who paid for them?

Perfection

Vincenzo Latronico

Translated from the Italian by Sophie Hughes

136 Pages

Paperback

ISBN 9781681378725

New York Review Books

Purchase this book