Four Ecologies

Ulf Meyer

9. février 2021

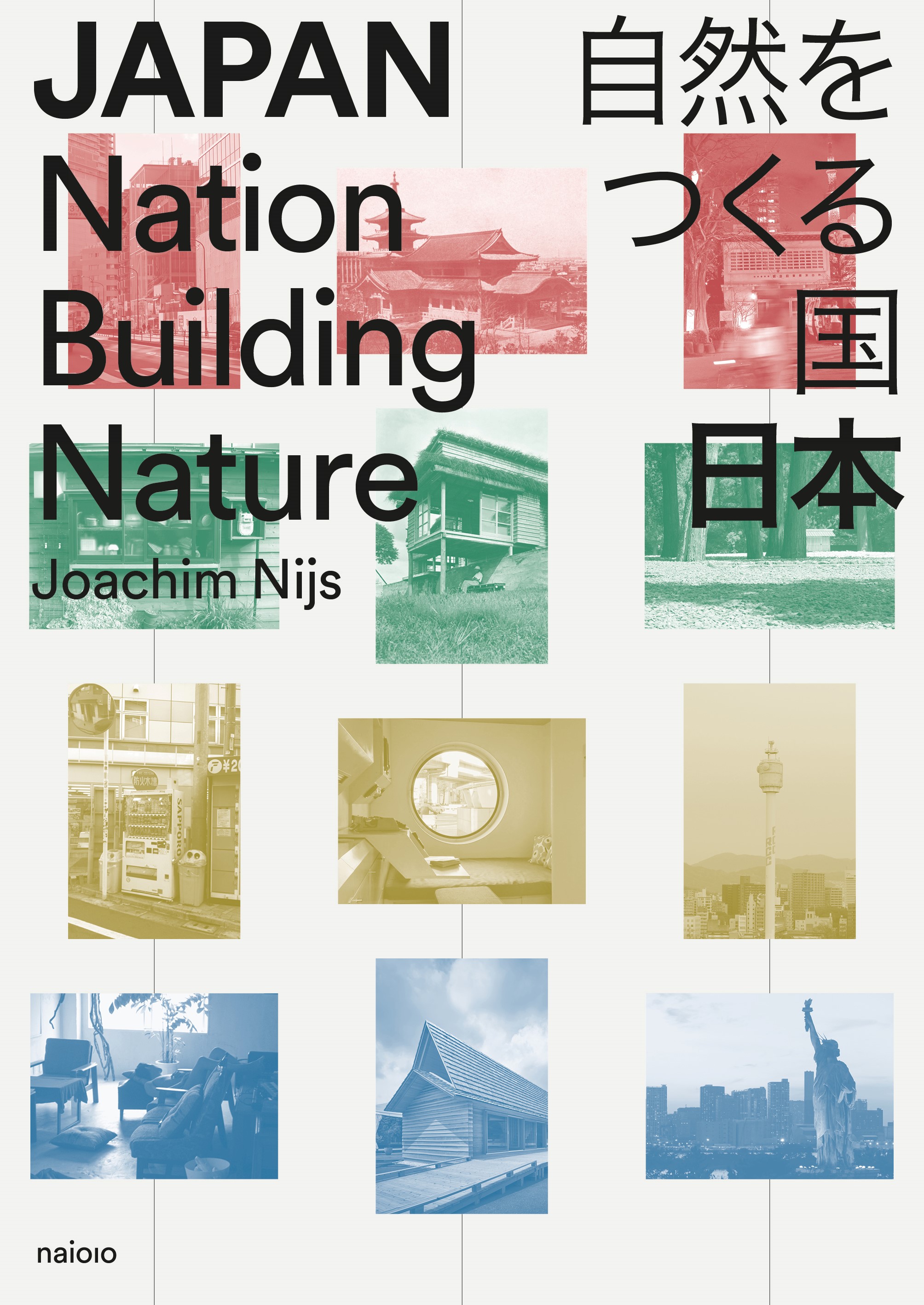

Photo courtesy of nai010 Publishers

In Japan: Nation Building Nature, Joachim Nijs searches for an “alternative interpretation of Japanese architectural history” through a matrix of four ecological phenomena. Ulf Meyer — a fellow European as enthralled with Japan as Nijs is — read the recently published book and sent us his take on it.

Trashy snapshots by the author, crowd-funded writing by a youngster, a hip layout —these are the ingredients for a popular contemporary book. Its topic is very interesting and even more timely: the “relationship between design, culture and natural disaster.” This is a central part of the current zeitgeist and Japan is a fitting case study, since it’s a place where nature is omnipresent as a source of disaster.

The author develops a matrix of observations. (Photo courtesy of nai010 Publishers)

Joachim Nijs is a young architect from Belgium, who, after spending time in Japan, could not help going back for more. He found his life assumptions shaken and felt the urge to write a book about his experiences in this other universe that the land of the rising sun is, in many ways. The author of this review can sympathize, having done and felt exactly the same twenty years earlier. Nijs’s approach is deeper, more intellectual; Japan: Nation Building Nature, published by Rotterdam’s nai010, developed out of his 2018 thesis, “Nation Building Nature: Constructed ecologies of Japanese architecture,” at the University of Ghent.

Nijs’s main interest is “Japan's unique ecological ethic” as expressed in its built environment. Using a fresh blend of academic research and personal experience, he navigates Japanese architectural history through a matrix of four phenomena: earthquakes, monsoons, nuclear erasure of life, and insularity. He then identifies four Japanese terms with which to read these topics: mujo, fudo, kyosei, and mottainai. These four terms, ranging from “ephemerality” to “zero waste,” help Nijs structure his book. This set up is gutsy and intelligent, and it does produce new insights.

Gaps between houses have led inhabitants to place their garden on the sidewalk. (Photo courtesy of nai010 Publishers)

Nation Building Nature “maps out the views of nature that have shaped modern architecture of Japan,” which the author calls “acclaimed but misunderstood.” Well, I am not sure it is misunderstood, and even less convinced that Nijs believes it too, but he certainly found a new take on the topic by looking at the concept of nature in the political arena. After all, he is not all that interested in architecture alone but in its wider political, cultural and foremost ecological context; that is the great value of his view.

While not a Japanologist, Nijs does demonstrate a wide scope of interests and knowledge, and he is not afraid of jumping to conclusions. Of course, he puts more on his plate than he can really chew, but that is fine since it lets him roam intellectual horizons in cinemascope. His takes on how Japan has tried — and is trying again now — to “overcome modernity” and how the “ensured ruin” is worked deeply into Japanese understanding of buildings and cities are eye-opening. So are his arguments regarding the “voluntary self-colonization” that he sees at work in Japan and over the mechanisms ensuring that “impermanence contributes to vitality.”

Nijs’s interpretations of Toyo Ito’s statements that “natural disaster does not really exist” — that, rather, it’s the stubborn and rigid way of building that leads to damage — compares nicely to the Buddhist “philosophical perspective of destruction.” Ito believes that the concrete architecture of the twentieth century resembles a house of cards when a quake or tsunami strikes and that only softness could persevere. “Strong architecture has failed the people,” he claims, in a country where “weather and climate traditionally are invited into the house.” Maybe it is true: Japan is in “a different modernity” altogether. Like the Galapagos Islands on the other side of the Pacific, being detached from the world does not conflict with being highly developed.

The “ring of fire” around the Pacific Ocean. (Photo courtesy of nai010 Publishers)

Nijs is a broad thinker and courageous writer. He does not shy away from insightful excursions into philosophy, design, and geopolitics. The (rather steep) price to be paid for this unobstructed and self-confident approach is the multitude of obvious mistakes, some of which are so embarrassing that they seriously diminish the value of the book and make this reader suspicious of the efforts to research and edit it. The Heisei era is quoted as starting in 1982, when really it coincided with the fall of the Berlin wall in 1989; the Ginza burned down in 1872, not a hundred years later; and Botond Bognar, America’s most important writer on Japanese architecture, will not enjoy seeing his name misspelled. But these are excusable mistakes compared to confusing the elegant suki-ya style of residential architecture with suki-yaki, a popular meat dish. Even if the writing software’s auto-complete is to blame for this, a good editor would have intervened. If author and/or editor knew more kanji, these kinds of mistakes would not have happened.

The author calls himself an “expat with a playful state of mind” and that is great, but it probably means he could only access sources from outside via second-hand translations. Nijs writes in the first-person singular, which gives the book a personal and breezy feel, but at times it also feels subjective and unprofessional. That is the danger when turning an academic thesis into a journalistic book.

Nijs’s writing makes it overly clear which sources he sucked dry and which ones he ignored. Rem Koolhaas’s Project Japan really triggered him, but not as much as Kinji Imanishi’s A Japanese View of Nature and Tetsuro Watsuji’s A Climate: A Philosophical Study. Less so is Kisho Kurokawa’s pocket-sized The Philosophy of Symbiosis, even though it was translated into English more than 25 years ago. Somehow, Katsuhiro Miyamoto’s idea of “pacifying malevolent gods” by turning the Fukushima No. 1 Nuclear Power Plant into a giant Shinto shrine seems to have escaped the author, even though it would have given the book an interesting added angle.

Katsuhiro Miyamoto, Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Plant Shrine, 2012, Installation view at Aichi Triennale 2013 (Photo: Tetsuo Ito)

The publisher, part of the prestigious Netherland’s Architecture Institute, claims the “book explains how Japanese culture can shed new light on our understanding of ecology, and vice-versa.” It actually does that. While this book about the “tyranny of climate” and recovering from the 2011 Tohoku disaster was being edited, another disaster, in the shape of the coronavirus, hit. It goes to show that the questions Nijs raises in this, his first book, will not lose relevance anytime soon.

Japan: Nation Building Nature

Joachim Nijs

Design: Sander Boon; Photography: Joachim Nijs

17 x 24 cm

272 Pages

150 Illustrations

Paperback

ISBN 9789462086135

nai010 Publishers

Purchase this book